©

The Sunday Star

by Martin Vengadesan• The turning point

• All for independence

• Significant moments

The state of judiciary is very much in the news today and in the forefront calling for reform is the Bar Council. The country's governing body for lawyers was set up under the 1947 statute that charged it to uphold the cause of justice without fear or favour. Sixty years on, despite difficulties, it remains true to its cause.

TWENTY-SIX YEARS ago, on April 7, 1981, about 200 lawyers gathered at Parliament House. Their aim: distribute two memoranda protesting the amendments to the Societies Act and the Constitution.

They braved a drizzle and an unfriendly Home Minister who refused to accept their memoranda. A year later, 42 of the lawyers were charged with unlawful assembly and found guilty in January 1983.

That protest, organised by the Malaysian Bar Council and led by its then president G.T.S. Sidhu, was hailed by one of country's most admired parliamentarians, Tan Sri Dr Tan Chee Khoon, in his column, Without Fear or Favour, in The Star.

Dr Tan wrote: “Congratulations to the Bar Council for getting out of their air-conditioned rooms and descending from their ivory tower to demonstrate for fundamental liberties and human rights in this country.

“In my wildest dreams I would never have thought of the day when our lawyers would participate in a demonstration.”

|

|

When more than 2,000 lawyers took a Walk for Justice last month, it made headlines because of the strong point they wanted to make. |

|

On Sept 26, 2007, to the amazement of their fellow citizens, 2,000 lawyers led by Bar Council president Ambiga Sreenevasan went on a “Walk of Justice” to the Prime Minister's Office in Putrajaya.

Their purpose: To hand over two memoranda asking for a royal commission to investigate the now notorious video clip showing a prominent lawyer purportedly brokering the appointment of judges and the establishment of a permanent judicial commission.

This time, the reception was friendlier with the memoranda being accepted by the Prime Minister’s political secretary, Datuk Wan Farid Wan Salleh.

The lawyers’ “walk”, in a heavy downpour, was generally hailed as a positive action and drove home a very serious point. In Ambiga’s words, “When lawyers walk, something is wrong.”

The 1981 demonstration was against a very specific issue – amendments to a law that would severely curb civil liberties. In contrast, the Bar Council this time, while ostensibly asking for two specific things, was after “change, change, change”, as the lawyers chanted on the 3.5km walk, to address what is perceived to be growing corruption affecting the judiciary.

On the 60th anniversary of its establishment, the Bar Council is suddenly very much in the news again and in forefront of what it was set up to do: To uphold the cause of justice without regard to its own interests or that of its members, uninfluenced by fear or favour, as stated under Section 42(i) of the Legal Profession Act 1976.

Beginnings

The legal system that would evolve to what it is today began when Sir Francis Light introduced the Charter of Justice in 1807 in Penang The first “law agent” was registered in 1808. The first Bar Association was set up under the Advocates and Solicitors Ordinance in 1914 but a modern independent and self-governing Bar Council was established under a 1947 Ordinance. This ordinance was eventually replaced by the Legal Profession Act of 1976.

In the years since, the Bar Council has grown with the nation, steadily at first, and then exponentially over the last two decades to a point where its membership numbers over 12,500.

|

Haji Sulaiman Abdullah says the Bar’s international reputation is ‘exceedingly high’. |

In the last several months, various legal cases and events have led to a growing sense of unease that all is not well with the judiciary, leading to calls for change. Respected former judges Datuk Shaik Daud Ismail, Datuk K.C. Vohrah and Datuk V.C. George (also a former Bar Council president) have also echoed the calls for a review and the setting up a judicial commission to appoint judges (

Weighing state of the judiciary, Sunday Star, Sept 30).

If there is increasing public cynicism towards the judiciary, former Bar Council president Haji Sulaiman Abdullah (who served from 2000-2001) sees it as a “healthy attitude”.

“I view it as a positive development. If people are outraged by the bias shown in certain cases and are sceptical of decisions, it shows that society at large recognises the importance of fair judges. A just society needs judges that can stand up without cringing and deviating from their purpose of upholding justice,” he says. In light of all this, it’s tempting to think of those years from the 1950s to 1980s as Malaysian judiciary’s golden age.

That came to end, by most accounts, in 1988, following the judicial crisis which saw the sacking of the Lord President and two Supreme Court judges. (See ‘The turning point’)

Respected judge, the late Tun Mohamed Suffian Hashim, wrote in Justice Through Law, a book commemorating the Bar’s 50th anniversary:

“During those days, relations between Bench and Bar were correct and not at all hostile. Bench and Bar were engaged in a common purpose: to see that justice was done.”

Sulaiman Abdullah (who served from 2000-2001) has been active in legal circles for four decades and recalls, too, those early days with fondness.

“Malaysia produced many extraordinary judges like George Seah and the Vohrah brothers (Datuk K.C. and his older brother Tan Sri Lal C. Vohrah), and the relationship between the Bar and the Bench was one based on mutual respect.

Duty-bound

While the Bar has sometimes been embarrassed by incidents that made lawyers appear self-serving or indifferent (such the lack of quorum at its AGM), Amiga feels the body has not swerved from its original objective.

“It is my honour to lead the Malaysian Bar which has stayed true to its duty by standing up for what is right and in the public interest without fear or favour and without regard for its own interests,” she says.

To her, the Walk for Justice makes a pretty strong case for this.

“There are those who try to brush it off and have sought to label it many things like an opposition event. Of course the problem with labelling is that one does not then have to deal with the facts or merits of the issues raised.

“But the facts are these: More than 2,000 lawyers cutting across racial lines, political affiliations, gender, age, and areas of practice gathered at Putrajaya on a working day to show their concern about the state of the Judiciary. Does that not speak volumes?

|

»We know what the problems are with the judiciary and we are genuinely concerned. We have been concerned for a long time«AMBIGA SREENEVASAN |

“Label it anything you want, it would be wrong to ignore the voices of so many. And why were we all there? Because as lawyers, we know what the problems are with the judiciary and we are genuinely concerned. We have been concerned for a long time. We have also been consistent in what we have said and what we have sought. We have also been asking for transparency in the appointments and promotions process. A strong Judiciary will enhance the standing of Malaysia internationally.”

Indeed, the issues confounding the profession and judiciary today, such as the perception of corruption, are not new.

As Mohamed Suffian said in Justice Through Law: “In my time, everybody who came to court knew that he would get a fair hearing and a 50:50 chance of winning (or losing). There was no need for parties and lawyers to scout around for a user-friendly judge. If a lawyer won more often than his fair share it was by merit; people did not suspect it was because he had influence.”

But what is happening today, according to lawyer Mak Lin Kum, is that the present Bar, led by Ambiga, is “really taking the problems by the horns and dealing with issues that past presidents have not been vocal about.”

“It is a demanding, thankless job, but the Bar is an important channel for a democratic Malaysia,” he says.

Bar services

It remains to be seen whether lawyers walking for justice will lead to any changes. But history so far has shown that, in a showdown, the executive has always held sway.

The 1981 Parliament House demonstration, for example, failed to stop the amendments from being passed.

But on its part, the Bar Council intends to keep growing to fulfil its charter's numerous objectives – the foremost being to serve justice without fear or favour – as well as maintaining and improving the standards of conduct and learning of its members and others and protecting and assisting the public in legal matters.

To do that, it has 30 committees and four ad-hoc committees on areas such as human rights, legal aid, orang asli rights, intellectual property, gender issues, study loans, best practices and numerous sub-divisions of the legal practice.

As Sulaiman says, “Towards that end (of serving justice) the Bar has set up more and more committees in order to cope with that over-arching mission.”

Ambiga's focus, however, is on human rights.

She explains why: “When I took over in March this year, one of my areas of focus was to step up our human rights agenda. Lawyers in all jurisdictions are at the forefront of human rights work. I believe the Human Rights Committee has its work cut out for them.

“I would like to add that the Malaysian Bar, at its own cost, provides free legal aid to those that qualify for it. This is our contribution to society. We have many volunteer lawyers who give of their time for this purpose. This is one aspect of our work that not many people know about.”

Sulaiman says, as a lawyer, he has always been interested in the way the nation is governed which was why he first stood for office in the Bar's executive committee shortly after the 1988 judicial crisis.

“I’ve always enjoyed committee work and found a lot of scope for that in the Bar Council. If you sit in committees, you manage to pick up a lot of knowledge and skills.”

It would appear that desire to serve the public and safeguard justice runs in the blood of younger lawyers too.

Edmund Bon, 33, chairs both the human rights committee and national young lawyers committee.

“We have a duty to assist the public and a wide scope within which to work,” he explains.

“Ambiga has brought in a whole new generation of lawyers and we have drafted a

blueprint for the workings of the Bar Council, which was launched in May.”

While Bon agrees that there was a time when the Bar was viewed as elitist and unable to connect with the public, it has since grown and changed.

“The law affects people from all walks of life so we feel we have to reach out,” he says.

Not everyone feels that the Bar Council has done enough, though.

“The Bar Council is a toothless tiger,” commented a law graduate who declined to be named. “The leaders are very eloquent in putting forward arguments, but for all their bluster, they have hardly made any difference to the way this country is run.”

The good guys. Really

Still, it is not for want of trying. One of the Bar’s means of communication is its extensive website (

www.malaysianbar.org.my) which is maintained by Conveyancing Practice Committee chairman Roger Tan.

Tan says the Bar is constantly trying to educate the people on their legal rights and inform them about legal services and even the costs.

Despite all that, he laments the wide misconception about lawyers – hence, the numerous jokes about them as avaricious beasts feeding on the misfortunes of others.

“Lawyers are only appreciated when people's liberty or property is threatened or taken away!” he sighs.

Sulaiman feels that the Bar deserves all the credit it gets. “I’m sorry to sound arrogant but I don’t see any shortcomings. It is an organisation that is entirely voluntary. In fact, lawyers without vested interests invest a lot of personal time and money in their work with the Bar.

|

Lawyers say they walk the talk by providing free legal aid. |

“Of course there are people who want to curry favour and get ahead but generally such people see more disadvantages in being associated with the Bar leadership and there are easier ways to achieve this goal.

“It is a gift to be a lawyer, and I’m glad to say, based on my involvement in international Bar associations, that the reputation of the Malaysian Bar Council is exceedingly high. Not just for the stands we take, but others are struck by our lawyers' contributions towards legal aid, as all members are required to contribute towards a fund for that.”

Still, Tan agrees that with so many lawyers around, there are bound to be a few bad hats.

“I do agree that there is a surfeit of lawyers and we have to examine the quality of lawyers that we are now producing. Our membership doesn’t even include legal officers and law lecturers, not to mention those with law degrees who chose not to practice.

“Of course there have been outbreaks of discord within the organisation. But the beauty of the Bar is that when the unity is threatened, the members have never failed to rally together. When the AGM was declared null and void over the quorum issue, thousands turned up to show their support.”

Issues ahead

Despite this, there are many challenges ahead which will require firm action, says former Bar Council president Yeo Yang Poh who stepped down earlier this year.

“In terms of commerce, I think things will remain reasonably good, though the challenge is to be able to compete globally.

“In terms of the justice system, it is very bleak, unless the authorities wake up from their state of denial and put in place meaningful reforms such as the Judicial Appointment and Promotion Commission.”

One issue that could divide the Bar is syariah law. Is Malaysia to remain with two separate legal systems or will Islamic law one day apply to all citizens?

“This is one area where there is great public conflict and there is the danger of inciting division within the ranks of lawyers themselves,” says Sulaiman. “I’ve always felt we should tread very carefully. On the one hand, there is the passionate desire among many Muslims to be governed by the dictates of Islam. On the other, an equally passionate fear of Islam.

“As a Muslim, I feel that fear is unfounded, but as a realist, it would be foolish of me to pretend that it does not exist. I think it will be a very sad day if we allow this issue to divide the Bar.”

For Ambiga, the biggest challenge lies in improving the profession's standards and to enforce discipline.

“We need to demand the highest standards of professionalism and integrity from our lawyers. To this end, the Qualifying Board is looking at introducing a Common Bar Exam to ensure that only the best enter the profession.”

Whether the public really understands or appreciates lawyers, on the 60th anniversary of their representative body, Sulaiman makes this impressive declaration on their behalf:

“Lawyers are, by and large, very fine human beings and members of the Malaysian Bar have stood by its leadership and supported it. It is a joy to work with.”

And that’s no joke.

The Bar Council’s 60th Anniversary Dinner will be held at the KL Convention Centre on Oct 31 at 8pm.

Performers for the dinner include Francissca Peter, Comedy Court and ASK Dance Co.

For more details, call Sivanes at 03-2031 3003 (ext 174). (For more information, please visit www.malaysianbar.org.my/mlc)

The turning point

There is scarcely a lawyer practising today who does not make reference to the Judicial Crisis that unfolded in May 1988. Beginning with the suspension of Lord President Tun Salleh Abas and five Supreme Court judges, it eventually led to the dismissal of Salleh as well as two of the five judges, Tan Sri Wan Suleiman Pawan Teh and Datuk George Seah.

The dismissals shocked the nation and raised questions about the independence of the judicial system. Nearly 20 years on, former Bar Council president Yeo Yang Poh (from 2005 to March 2007) is blunt when asked to explain the significance of the “confrontation” between the executive and the judiciary.

“Simply put, in 1988, the Government was worried that the outcome of certain court cases (involving Umno) was likely to be not what they desired. Hence (then Prime Minister) Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad decided to put in place machinery to remove the top judge who would not do the Govern-ment’s bidding. It succeeded. From then on, the Government managed to have a more and more compliant judiciary. That year was indeed a sad turning point for the country.”

Damning words indeed, but even current de facto Law Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department Datuk Seri Mohamed Nazri Aziz agrees that 1988 was a watershed year for the Malaysian legal system.

“We don’t want a repeat of the 1988 judicial crisis. It was the worst year for the Government in terms of its relationship with the judiciary and the Bar. As the Minister in charge of law, I don’t want to see it happen again.”

Indeed Nazri emphasizes that an independent judiciary is of paramount importance to Malaysia. (See below.)

Former Bar Council president (2000-2001) Haji Sulaiman Abdullah remembers the crisis as a tumultuous period that brought the organisation’s role into focus. “It made very clear that the administration’s perspective of any organisation/institution was that its primary purpose was to serve the government in power and that any perceived deviation was seen as something that needs to be corrected immediately. The more significant the institution, the stronger the reaction from the government if it strayed from its ‘limit’.

“Of course every government tries to get a judiciary that is favourable to itself, but in 1988, members of the Bar were confronted with a naked and absolute show of force. I think the common man has always recognised the necessity of a neutral umpire and any attack on a independent judiciary is an attack on the core of a civil society.”

“I am proud to say that irrespective of the personalities of the main actors, the bar chose overwhelmingly to stand by what was right rather than what was convenient. There were, of course, some very senior lawyers who were swayed by the seductive calls of convenience and tried to get the Bar to change its stand, but these efforts were repulsed.”

Indeed, Bar Council committee member Roger Tan recalls that some members were unable to withstand the pressures they faced.

“I actually remember that after the removal/suspension of the judges, the Bar Council passed a resolution not to recognise the new judicial leadership, but I’m afraid that for Malaysians, the rice bowl comes first, and as such, many lawyers did not follow through with this.”

“The Bar is known for ostracising judges who have gone astray, but it is also the first to defend and honour judges who have stayed steadfast to their oaths in preserving, protecting and defending the Constitution.”

Current Bar Council president Ambiga Sreenevasan feels that the situation is not beyond repair. “I believe the judiciary certainly needs looking into seriously. We have many good, honest and hardworking judges who are working with limited resources. We appreciate the work they do and the circumstances under which they function. They deserve to be in an institution that is scandal-free and above suspicion.

“I maintain that we are capable of a First World, first class judiciary and we are entitled to it. But confidence in an institution is a fragile commodity. Once this is damaged, it requires sincere and positive action to restore.

“But the first step towards restoring confidence is to recognise that there is a problem.”

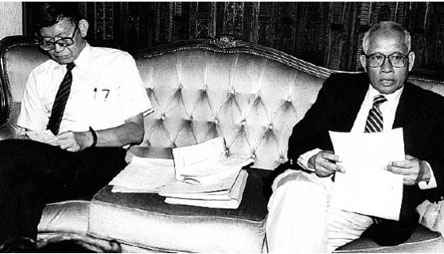

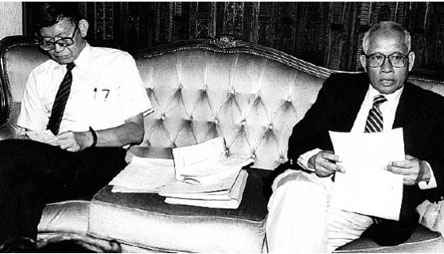

Tun Salleh Abas with Raja Aziz Raja Addruse who represented him at the tribunal hearings.

Tun Salleh Abas with Raja Aziz Raja Addruse who represented him at the tribunal hearings.

All for independence

AN independent judiciary is crucial to the well-being of the country, says de facto Law Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department Datuk Seri Nazri Aziz.

“It is true that Barisan Nasional is very dominant politically, but the administration under our current Prime Minister, Datuk Seri Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, has followed a policy of non-interference in the legal system. This government is in favour of an independent judiciary.

“We know that if the Prime Minister interferes, that’s it, the whole system becomes compromised. Pak Lah has moved towards openness and transparency and he recognises that an independent judiciary is crucial for the country’s development.

“And I think it could immediately be seen with the case of former Deputy Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim, who was released from prison soon after a change of leadership,” he says in an interview on Tuesday.

(On Sept 2, 2004, the Federal Court overturned Anwar’s 2000 sodomy conviction by 2 to 1, as it found contradictions in the prosecution’s case.)

Nazri also says the Government was aware of the public's scepticism towards many important trials: “We are now in an era of experimenting with liberalism and this means a freer press, which can lead to sensationalism. I don’t want to start gagging the press, but this means that there can be unfair speculation, (and) that leads to a mindset where the public might see a conspiracy behind every major case.”

Neither has he taken kindly to the Bar Council’s recent protest in Putrajaya. He had criticised the Walk for Justice, saying it was “unbecoming”, according to press reports.

He was quoted as saying that there was no crisis in the judiciary and therefore no need for a judicial commission.

Nazri, however, says that he has often been misunderstood on the issue.

“I never said I am against a cleaning-up of the judiciary, merely that I want to work not just with the Bar Council but with the Judiciary itself. There are many judges right now who are concerned with the image of the judiciary in the eyes of the public, and we should all work together. And I would rather we discuss these problems face to face.

“The Bar Council leaders can always see myself or the Prime Minister to raise their issues. I feel that such protests are not in keeping with the stature lawyers should have in the eyes of the public. I would like us to work hand in hand with the Bar Council to improve the legal system. That is why I was very surprised when the lawyers marched.

“As a former lawyer turned executive, I am very particular about the separation of the government from the judiciary.”

Significant moments

HERE are some key events in the 60-year history of the Bar Council.

1947 – Founding of the Bar Council under E.D. Shearn. First executive committee contains notable lawyers like R. Ramani and Yong Shook Lin.

1958 – Bar Council protests against the Public Order (preservation) Bill because of the extensive powers being given even to junior police officersto control riots.

1965 – Government draws up Bill to limit the rights of appeal to the Privy Council in England, which is protested by the Bar. The Bill surfaces from time to time before this right is finally withdrawn in 1985.

1971 – All non-resident lawyers are no longer allowed to practise which leads to an immediate exodus of 63 Singaporean lawyers.

1974 – Former Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman is called to the Bar.

1975-77 – Repeated clash of wills between Bar Council and Government over Essential (Security Cases) Regulations (Escar). During this period, a 14-year-old boy is charged under the Internal Security Act for possession of a firearm and ammunition and tried under Escar. He is found guilty and sentenced to death because the law does not differentiate between a juvenile and an adult. Bar Council calls for a repeal of Escar and at an EGM resolves that members should not appear in trials involving Escar. The AG expresses regret over the resolution. In the following months, several lawyers withdraw as counsel for Escar cases. (The boy’s death sentence was eventually commuted to detention in a juvenile home and he was released some years later.)

1978 – Legal Profession (Amendment) Act 1977 is passed with provisions to allow the AG to issue certificates for foreign lawyers to practise in Malaysia, barred certain classes of lawyers from holding office in the Bar and raised the quorum to one-fifth of its membership. This amendment is regarded as the Government’s retaliation against the Bar’s opposition to Escar.

1981 – 200 lawyers march to Parliament wearing black armbands to protest amendments to the Societies Act and the Constitution. Foty-two are later charged with and found guilty of unlawful assembly.

1983 – Bar Council passes resolution to levy a compulsory subscription of RM100 per member per year towards its Legal Aid Centre Fund.

1985 – Bar Council sets up a committee chaired by former Prime Minister Tun Hussein Onn to review provisions of the Legal Profession Act.

1986 – Lawyer Karam Singh and then Bar Council vice-president Param Cumaraswamy are charged with sedition but is acquitted. The High Court ruling is hailed as a vindication for free speech in Malaysia.

1987 – Government uses Internal Security Act to detain opposition and social activists under Operation Lalang

1988 – Judicial crisis unfolds resulting in the sacking of Lord President Tun Salleh Abas and two senior judges. The Bar opposes the Executive’s actions.

1990 – Bar AGM votes to introduce a mandatory professional indemnity insurance scheme to cover every law firm.

1995 – Hendon Mohamed, the first Malay woman lawyer, is also the first woman elected Bar president.

1996 – Poison-pen letter causes a scandal resulting in resignation of a High Court Judge.

1998 – Perceived inconsistencies in sodomy and corruption cases involving former Deputy Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim lead to renewed momentum in Bar’s activism.

2000 – The Bar moves a motion calling on the Prime Minister to make representations to the King for the appointment of a tribunal to investigate the conduct of Chief Justice Tun Eusoff Chin.

2005 – Former Bar Council president Datuk Param Cumaraswamy and several other prominent members walk out of AGM that is allowed to carry on despite the lack of a quorum after the Bar takes the view of several lawyers who feel that a quorum is not required.

2007 – Walk for Justice sees 2,000 lawyers calling for judicial reform.

Source: Justice Through Law; Staric

©The Sunday Star

©The Sunday Star

It remains to be seen whether lawyers walking for justice will lead to any changes. But history so far has shown that, in a showdown, the executive has always held sway.

It remains to be seen whether lawyers walking for justice will lead to any changes. But history so far has shown that, in a showdown, the executive has always held sway.

“Of course there have been outbreaks of discord within the organisation. But the beauty of the Bar is that when the unity is threatened, the members have never failed to rally together. When the AGM was declared null and void over the quorum issue, thousands turned up to show their support.”

“Of course there have been outbreaks of discord within the organisation. But the beauty of the Bar is that when the unity is threatened, the members have never failed to rally together. When the AGM was declared null and void over the quorum issue, thousands turned up to show their support.”

AN independent judiciary is crucial to the well-being of the country, says de facto Law Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department Datuk Seri Nazri Aziz.

AN independent judiciary is crucial to the well-being of the country, says de facto Law Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department Datuk Seri Nazri Aziz.